WORDS BY Xu Kaisen

PHOTOS BY Lin Weikai, Hsu Yung-Chin

TRANSLATION BY Joe Henley

“The source of calligraphy is openness and limitlessness; it’s a flowing concept. A calligrapher’s inspiration can be anything or any scene in this world such as trees, stones, mountains, plains, the ocean, wind, and rain. The image and the word simply penetrate each other.” As such does calligrapher Hsu Yung-Chin (徐永進) define the art of calligraphy with his own erudite philosophy.

ENJOY ART AS IT IS AND LET NATURE RUNS ITS COURSE

Hsu Yung-Chin, now 67 years old, is a contemporary Taiwanese calligraphy artist who started his career, as do most, by learning traditional calligraphy skills. It was not until the late 1990s that he began to gravitate toward modern calligraphy and ink painting. Hsu’s first encounter with calligraphy dates back to his days at Hsinchu Teachers College (新竹師專), where he began studying when he was 17 years old. At first, he learned calligraphy through self-study. Then he tried to imitate calligraphy master Liu Gongquan’s (柳公權) letters again and again in order to improve his skills. Finally he began to receive instruction by professional calligraphy teachers. In just a year, he had cultivated a keen interest in writing calligraphy, which led to his decision of making it his life-long career.

Hsu recalls a time when a delegation of Japanese calligraphers came to Taiwan for a cultural exchange, and before departing Taiwan, they left a rather cutting remark, saying that “In a few more years, all Taiwanese will have to come to Japan to learn calligraphy.” Their comment raised dissatisfaction in Hsu’s heart, and he determined to exhibit his own calligraphy pieces on Japanese soil one day. Consequently, Hsu exerted himself in his practice. When he lacked the money to buy paper and ink, he practiced by writing on bricks during the 10-minute recess between classes. By doing so, Hsu could accumulate around 80 to 90 minutes of extra practice every day. (If you’re into art: Celebrate the beauty of the eastern coast at Taiwan East Coast Land Art Festival)

After five decades of relentless practice, Hsu has come to a somewhat surprising conclusion: Working too hard is a sign of insufficient confidence. He has realized that during the early years of his calligraphy studies, he spent too much time practicing just to compete with other calligraphers, and that, according to his current beliefs, is the wrong approach. Instead, the quintessential nature of art is to let it run its course and let loose your inspiration. Only then have you reached that stage wherein you will be able to relish the true beauty of art.

THE STORY BEHIND THE MASTERPIECE “TAIWAN”

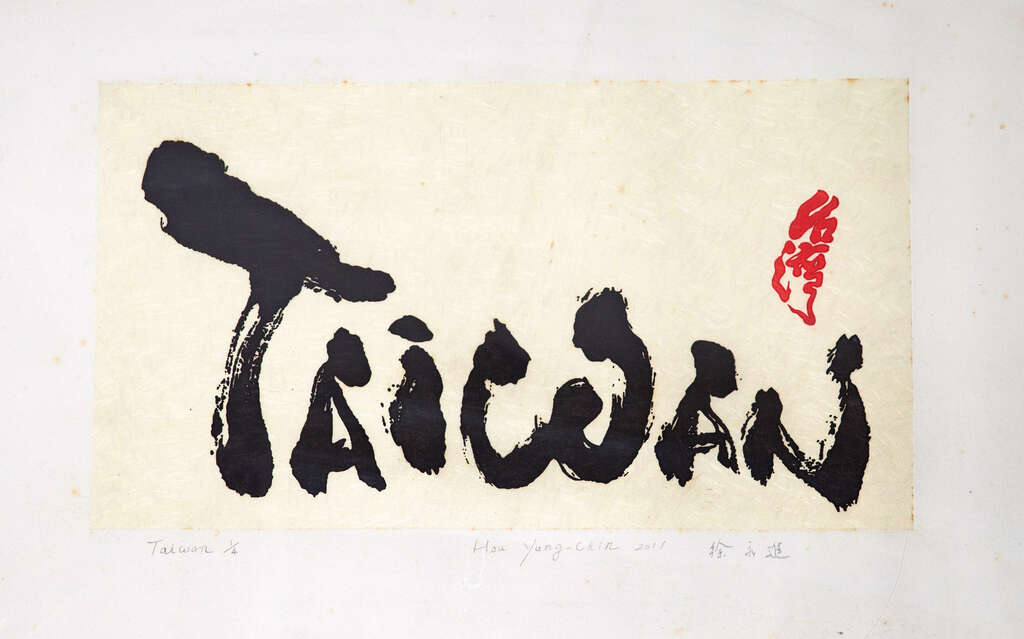

“Localness” is a great emphasis within Hsu’s calligraphy and paintings, and he tries to infuse his cultural empathy for the local to transform traditional calligraphy into a modern art form. In that vein, Hsu created a calligraphy piece with the word “TAIWAN” in 2001. Hsu bestowed an ingenious meaning upon each letter, and together, the letters became a cultural totem promoting Taiwan’s vibrant tourism. The letter “T” resembles Yehliu’s Queen’s Head (野柳女王頭) on the northern coastline; the letter “A” depicts a Taiwanese showing friendliness toward a tourist; the “I” shows a tourist looking at the Queen’s Head. Meanwhile, the “W” looks like two people talking happily, a take on the strong sense of hospitality in Taiwanese people. Lastly, the letters “A” and “N” conjure up a heartwarming image of a grandma holding her grandchild. (Know more about Yehliu: The North Coast’s Heavenly Art)

A stroke in 2004 rendered Hsu’s right-side paralyzed. During that time, though emaciated and nearly unable to speak, Hsu kept writing with his left hand every day. “Before the stroke, my body could automatically adjust itself to reach equilibrium, but after the stroke I had to maintain balance with awareness,” Hsu says. “This is exactly what my recent creations are dealing with. I am trying to strike a balance between the old and the new.”

In 2011, Hsu held a solo exhibition called “Beyond Calligraphy” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei (台北當代藝術館). Pieces exhibited included calligraphy written with acrylic paints, 3D calligraphy sculptures, digital calligraphy shown on LCD screens that showcases the combination of digital technology and animation, interactive digital calligraphy, as well as “the art of dynamic audiobook” presented in a 180-degree panoramic theatre, a collaboration with U-Theatre (優人神鼓), a Taiwanese performance art troupe.

The exhibition was an avant-garde cross-border performance comprised of whimsical mixed media and forms of expression that brought the art of calligraphy from a mere 2D reading to a 3D experience.

“In the past, we wrote words on paper, but now we can write words on clouds. Words can dance and spin to another height. Self-confinement and monotonousness do nothing but hinder the development of calligraphy,” Hsu says. At the age of 60, demonstrated his fantastic creativity and ability to cross and connect different fields of art, marks a huge transition in his career as a creator. (Read more: From Fingertips to Paper: Papercraft Artist Johan Cheng Cuts a Slice of Life’s Most Beautiful Moments)

CALLIGRAPHY, MARRIAGE, AND NATURE

Mr. and Mrs. Hsu now live in Taipei’s Shilin District, also the place where their romance first began. Around 30 years ago, Hsu and Zheng Fang-He (鄭芳和) (now Hsu’s wife), were both invited to a traditional Chinese music concert. At the concert, the couple met for the first time, and Hsu was expressing his opinion about the rhythm of calligraphy and music to Zheng with Ambush from Ten Sides (十面埋伏), a masterpiece of Chinese Classical music, being intensely played on stage. Hsu’s enthusiasm caught Zheng’s attention; they started dating and walked down the aisle not long afterwards.

At that time, Hsu was teaching at Ming Chuan Business College (銘傳商專) and Mrs. Hsu at Chinese Culture University (中國文化大學). Thus they decided to form their family somewhere between the two, and that place turned out to be Shilin, an area scattered with rice fields and lotus ponds back then. The National Palace Museum and the Taipei Fine Arts Museum have since witnessed their frequent visits.

The couple’s love for nature also makes them regular visitors of Yangmingshan (陽明山), the Waishuang River (外雙溪), and the Shengren Waterfall (聖人瀑布). There are more than ten parks and bikeways in the neighborhood of Shilin where the couple can enjoy the scenic view of the left bank of the Shuang River (雙溪) on their bicycles whenever they want. The Chiang Kai-shek Shilin Residence (士林官邸) is practically their back yard. They come here to watch chrysanthemums and hike in their spare time, and the banyan trees here are their favorite painting subjects.

STAUNCH CONCENTRATION CREATES PENETRATING STROKES

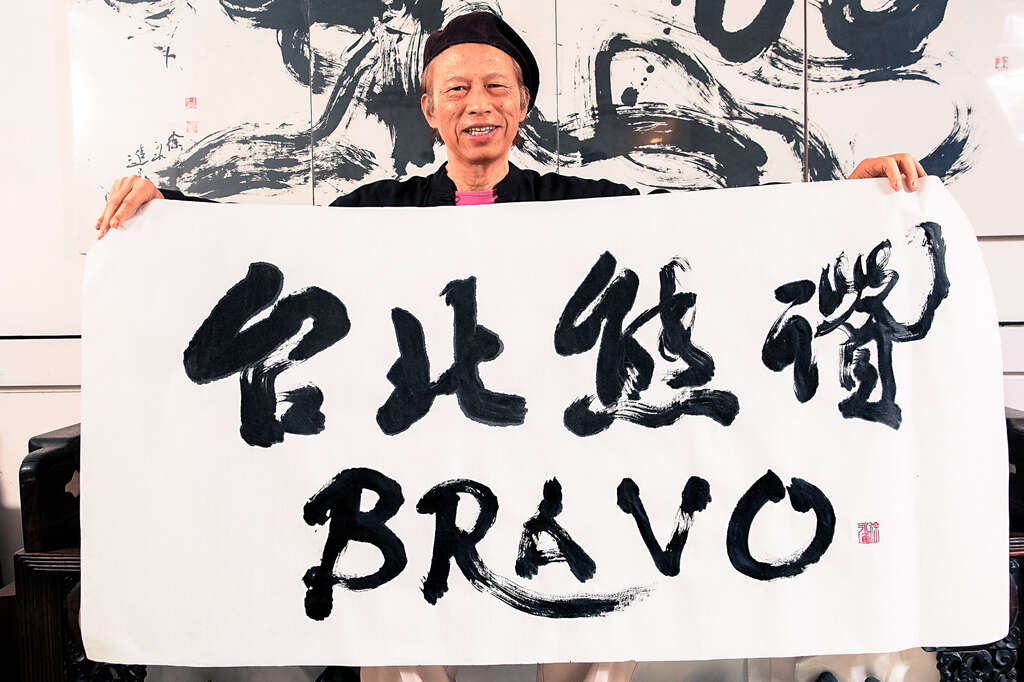

We asked Hsu to write “Taipei Bravo”, the city mascot’s name, to showcase his skills. Despite the fact that he is already a seasoned calligrapher with decades of experience, he still took a professional and strict attitude toward our request. After several practices, Hsu took hold of his calligraphy brush and wrote these letters with firm strength which seemed to penetrate the paper. “I don’t even have the time to see clearly how my writing is,” Hsu exclaimed after he finished writing. His comment is not hyperbole. When Hsu is holding a brush in his hands, his focus becomes so concentrated and he lets his feelings take over. When Hsu is performing his art, the word “writing” might not be exactly precise; it is more appropriate to say that “the god of calligraphy” is performing the strokes via Hsu’s hands.

“Good craftsmanship depends on the use of the right tools.” This Chinese phrase is not quite applicable to Hsu, a person who is not extremely choose when it comes to brush selection. In his opinion, the point is never the brush, but the person who holds it and the content of their heart. The philosophy corresponds to the poem hung on the wall in his home that says:

Flowers are to spring as the moon is to autumn, a cool breeze is to summer as snow to winter; Allow no trivial matters to concern your heart, you will have the privilege to savor all the good times in this world.

Calligraphy, according to Hsu Yung-Chin, is like his first crush, and there is nothing that can make him happier than writing calligraphy. Hsu still sticks to his daily routine of meditating, working out, and writing calligraphy. A life that may seem severe from the outside, but is rich and wonderful at its core.

This article is reproduced under the permission of TAIPEI. Original content can be found at the website of Taipei Travel Net (www.travel.taipei/en).