Words by: Catherine Shih Photos by: Yenyi Lin, Taiwan Scene, jon-flobrant

Taipei’s diverse range of architecture and building construction stems from 100-plus years of history and development. From the Japanese era to the present day, every stage of urban development has undergone different transformations, following the capital city’s rapid pace of growth. To find the vestigial memories of each era, following the evolution of architecture is the best way. In doing so, one can find the ingenious art of Koji pottery (交趾陶) preserved in Baoan Temple (大龍峒保安宮) since the Qing Dynasty, or see westernized buildings such as the Presidential Office, which has remained graceful since the time of WWII.

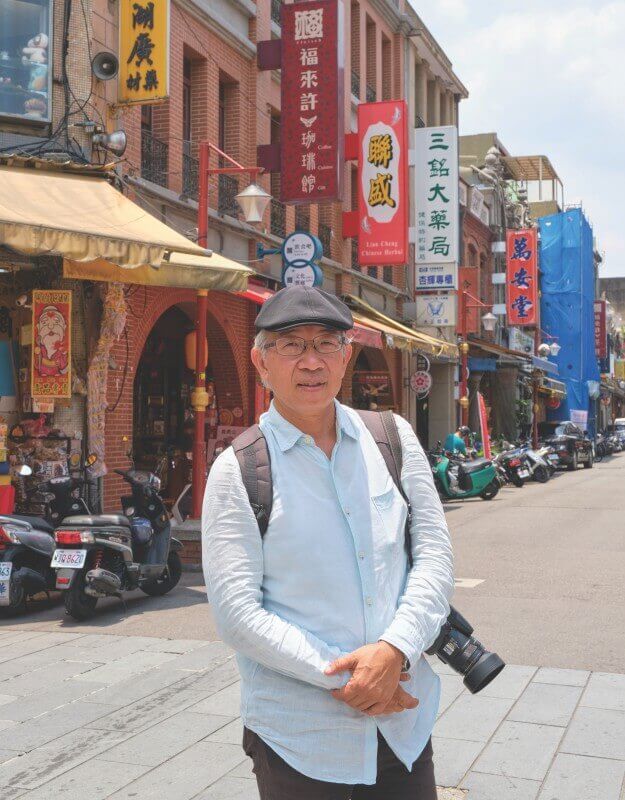

2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the establishment of Taipei City; therefore, we have invited Taipei’s premier architectural historian and guide, Cheng Sheng-ji (鄭勝吉), to sit down with us to recount the unique history behind Taipei’s transformation. (Read more: Taiwan’s Architecture Comes of Age)

GETTING TO KNOW CHENG SHENG-JI

With a keen interest in architecture since the age of ten, Cheng Sheng-ji, who majored in architecture in college, has been engaged in the field for nearly 40 years. Armed with his fascination and knowledge of buildings and design, Cheng has devoted his life to studying historical monuments in Taiwan and guiding viewers to appreciate its traditional elements. His pastime is guiding tour guides and tourists alike in viewing the beauty of Taipei’s architecture in terms of its historical context, so that others, too, can fully recognize and appreciate the excellence of Taipei’s buildings from different stages of the city’s history.

Q. What are the different stages in the evolution of Taipei’s architecture and appearance?

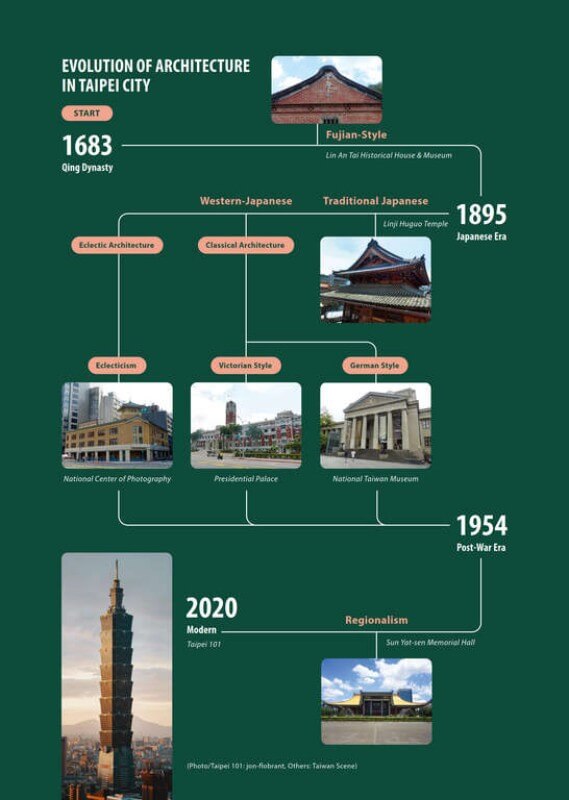

Well, the history of Taiwan as a whole is often marked by different periods of colonization — and the same goes for the history of architecture as well. As architects and historians, we often refer to the different periods of colonial history when discussing architectural evolution, starting with Dutch Formosa (荷治時期), Spanish Formosa (西班牙統治時期), the Ming and Zheng Dynasties (明鄭時期), followed by the Qing Dynasty (清領時期), and lastly, the Japanese era (日本時期) and Post-war era (戰後時期). It’s important to recognize the influence of history and politics when looking at these architectural relics. Regarding Taipei’s development in particular, since the development of Taiwan actually began from the south in Tainan (台南), with eventual migration to the north in Taipei, we see that the construction and development of the capital city actually began relatively late. Therefore, the major periods influencing the development of Taipei’s architecture boil down to three main periods of influence: the Qing Dynasty, Japanese era, and Post-war era. (Read also: National Palace Museum Experiences: A day of History and Culture in Taipei)

Q. What are the architectural styles and prominent elements/features of each stage in Taipei’s architectural history?

During the Qing Dynasty, Fujian-style was the mainstream; wood materials and red bricks, along with white stone or wooden carvings and murals were their distinctive features. On some of the temple rooftops, you might see Koji pottery as well. (You might also like: Vintage Taipei in Dadaocheng)

Japanese era was the period when western cultures kicked in due to Japanese advocacy of westernization. Of course, you can find traditional Japanese-style buildings constructed entirely with wood, with black tile rooftops, but the Western-Japanese style was still dominant. Western-Japanese style has many subcategories. One is Classical architecture that is influenced by European architectural traditions, such as British Victorian architecture and Classical architectural styles with features of German buildings, using stone to create a solid and majestic appearance. Another subcategory is Eclecticism. Such buildings were usually constructed with modern cement, but adorned with classical elements such as large arch windows, Western sculptures or black tile rooftops of a Japanese-style.

Finally, there are two important architectural styles during the Post-war era. Regionalism is a type of “retro” architecture with the purpose of preserving local architecture by incorporating traditional Chinese or Fujian-style features. After 1981, Modern architecture came to the fore. Buildings of varied shapes and personal styles began to spring up one after another in Taipei just as in every country in the world. (Read more: The City of Taipei: A Museum without Walls)

Q. What are the difficulties and challenges faced in preserving such historical sites and buildings?

The problem with the preservation of historical sites in Taipei is that people were not well aware of the importance of this issue until the 1960s. At that time, no national laws or budgets were set in place to help protect or preserve these historical sites. Besides, to keep up with the rapid pace of modernization at the time, many ancient buildings were demolished before even considering whether or not they should be preserved. Oftentimes, people would suddenly wake up and realize, “Whatever happened to that old building next door?”

However, an incredible watershed that defined a turn in the way of thinking was the Lin An Tai Historical House (林安泰古厝). At the time, the residence was located just opposite Shangri-La’s Far Eastern Plaza Hotel (香格里拉台北遠東國際大飯店), on what is now modern-day Dunhua South Road (敦化南路). In order to widen Dunhua South Road, rumors began to circulate among the community about its demolition, and consequently awareness of preservation of such historical buildings suddenly began brewing. Many local artists and literary figures stood up in defense of the traditional Fujian-style architectural piece. This incident contributed to the enactment of Cultural Heritage Preservation Act (文化資產保存法) in 1982. Eventually, the Lin An Tai Historical House was moved to its current site for preservation, and as a result, the government began actively classifying historical sites and formulating plans for long-term preservation in accordance with the new law. (Read more: 6 things to do in Taipei that should be on every visitor’s bucket list)

Q. Are there any representative Taiwanese architects and their works in Taipei that we should know about?

During the 1950s to 1960s, Taipei experienced an uprising in the number of architects who studied abroad and came back to Taiwan. Many of them studied under famous European and American architects, and their return to Taiwan has undoubtedly had a major influence on Taipei’s modern construction.

One such figure is Wang Dahong (王大閎), who graduated from the Department of Architecture at Harvard University and was also a classmate of The Louvre architect, I. M. Pei (貝聿銘). Wang’s works include Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall (國立國父紀念館), the College of Law building at National Taiwan University, and many more. Another interesting building to note was actually his own place of residence as a bachelor, originally located on Jianguo South Road (建國南路). It consisted of many red brick materials, floor-to-ceiling windows, and a courtyard — all brand-new concepts to the people of the time. Although the residence was later demolished, several of his students recently raised funds to rebuild an exact replica — Wang Da Hong House Theatre (王大閎建築劇場), which is currently showcased next to the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. (Read also: Exploring Museums with Kids in Taipei)

The other architect from that same period of time worth mentioning is Xiu Zelan (修澤蘭), goddaughter of Chiang Kai-Shek. At the time, there were only four female architects in Taiwan’s architectural circles, so she stood out among the rest and later received the acclaimed title of “Taiwan’s First Female Architect.” Her works were very representative of retro-style regionalism architecture; her famous works include the Yangmingshan Chungshan Hall (陽明山中山樓), the library and administration building at Taipei Jingmei Girls’ High School (台北市立景美女子高級中學), and many others.

Q. Which piece of Taipei architecture would you recommend most for foreigners to visit while in Taipei, and why?

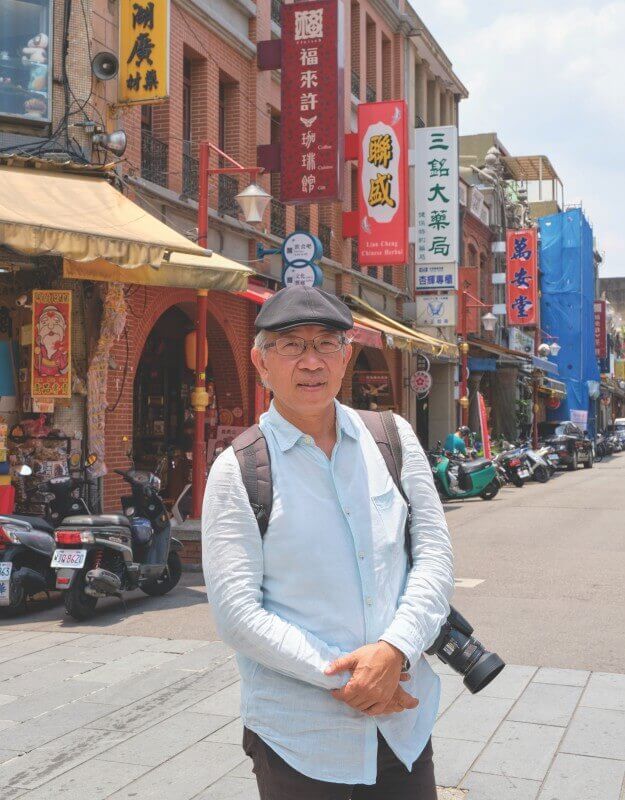

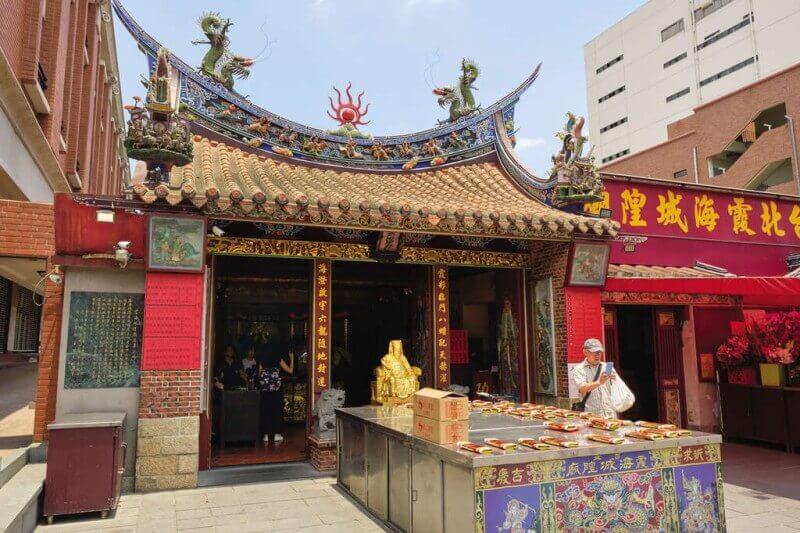

If you’d like to see and experience firsthand the evolutionary changes in Taipei’s architecture, I’d first recommend taking a trip around Dadaocheng. Almost all of the architectural transformations from the past century can be found in this small, five- square-kilometer block of the city. For example, you can find Fujian-style architecture, such as small Koji pottery details adorning the rooftops of temples like Taipei Xia-Hai City God Temple (台北霞海城隍廟), and also see some painted murals. Even more plentiful are the architectural relics left behind from the period of the Japanese era, such as Qian Yuan Chinese Medicine Store (乾元藥行) in the eclectic style that can be found on the buildings lining Dihua Street, for example.

The European-style carvings on the roofs are truly a sight, from family crests showing their family name, carvings depicting their trade (such as tea or Chinese medicine), to carvings of cats and vegetable heads representing lifelong prosperity, and so on. Architects working in this style, such as Yan Yi Cheng Commercial Firm (顏義成商行), married the old with the new to build a sense of peace and harmony within the city and is truly a rare jewel. Moreover, while taking in the architecture, you can also stop to enjoy the local food, music, and culture. If you haven’t been already, I would highly recommend taking a trip out there to fully soak in and appreciate the history of architecture in Taipei.

This article is reproduced under the permission of TAIPEI. Original content can be found at the website of Taipei Travel Net (www.travel.taipei/en).