Connecting Sense and Sensibility

As an inclusive city, Taipei is composed of diverse cultural and natural features that are often considered as running parallel to humanity. But not for Cheng- Huang Lin (林震煌), a chemistry professor at National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU, 國立台灣師範大學). By leveraging his deep knowledge of chemistry, he initiates many fascinating research projects linking science and art, proposing innovative angles to viewing the capital.

Having grown up and conducted his studies in Taipei, Lin started his academic career here, eventually going on to study abroad in Japan for his doctoral degree in the early 1990s, and later to the U.S. for further research. Soon after returning to his homeland in 1998, he began his studies related to Taipei’s natural environments.

“I still remember traveling with Japanese researchers to Yangmingshan National Park’s Menghuan Pond (夢幻湖), Zhuzihu (竹子湖), and Datunshan to collect soil and water in places that tourists couldn’t touch or reach for conducting research on acid rain. So, I can say I definitely know that mountain quite well!” he shares, noting his understanding about the terrain of the area.

Based on his solid experience in chemical analyzation, Lin was invited to join NTNU’s Research Center for Conservation of Cultural Relics (文物保存維護研究發展中心) in 2015 to help the team better understand the composition of artifacts via scientific examination. Currently, he works as a cross-departmental professor in the Department of Chemistry and the Department of Fine Arts, equally splitting his time between them, two days a week in each. “I’m often traversing between the campuses of NTNU, enjoying the vibrant atmosphere between Guting (古亭) and Gongguan (公館),” notes Lin.

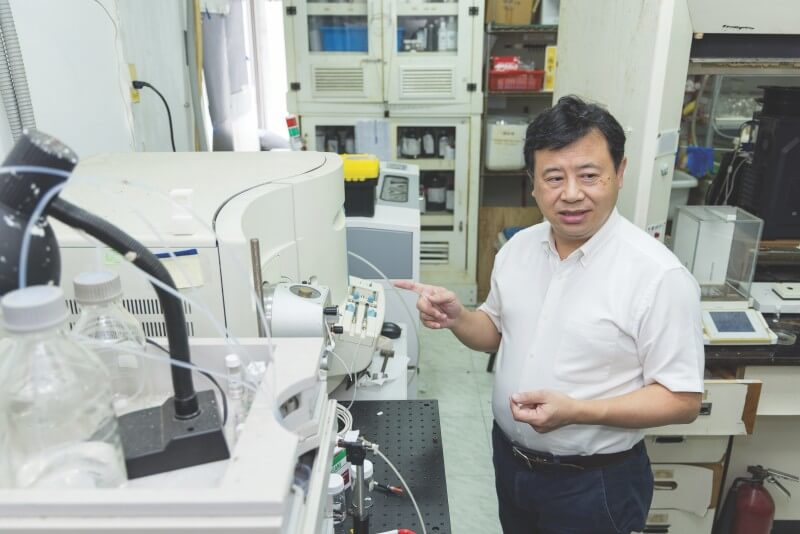

He further explains how his chemistry background could assist in the field of art conservation, “Most of the cross-field research I do requires knowledge of artwork materials and techniques such as gas analysis and Raman spectroscopy for the restoration of cultural relics like paintings and sculptures. Currently, I’m also highly interested in the research of indigo dye.” (Read more: Shaping the Memories of a Century: Master Guo Gengfu’s Life of Mortar Shaping)

Blending Chemistry with Art

Lin offers invaluable insight and knowledge to the art restoration program at NTNU’s Department of Fine Arts by teaching techniques and chemical analysis used in the preservation of cultural relics, such as infrared spectroscopy, lighting detection methods and material and surface analysis. Conversely, at the Department of Chemistry, he teaches a course on “The Application of Instruments and Chemistry in the Restoration and Preservation of Cultural Relics” in the hope that he can inspire budding chemistry students who might also be interested in art to become future experts in the art preservation and restoration field.

Through these courses, he is able to introduce the chemical changes and analysis of pigment materials commonly found in artworks. “The origins of blue paint come from lapis lazuli limestone found in the mountains of Afghanistan,” he says, “Back in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was very expensive. In fact, the blue headscarf featured in the famous painting Girl with the Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer was painted using this exact material. Later on, since cheaper methods such as azurite were discovered and used in oil paintings, it became more difficult to distinguish the ingredients of paint, making restoration even more challenging. Therefore, chemistry uses spectral analysis to distinguish the difference,” Lin further explains.(You might also like: Splashing Ink and Watercolor Throughout Taipei)

He used his own chemistry background when collaborating with the Research Center for Conservation of Cultural Relics to support the restoration and preservation of various artworks. The restoration of many of the paintings of early Taiwanese artists displayed at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (台北市立美術館) and the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (北師美術館) were based on Lin’s expertise and scientific knowledge, paired with that of local restoration experts.

Unearthing the Truth About Indigo Dye

Speaking of Lin’s research on indigo dye, he recalls, “I went with my kids when they were young to an indigo dyeing activity. I was so interested in the dye that I even brought back a bottle. Later, when my work in chemistry overlapped with art, I decided to include indigo in my research.”

He started with the indigenous plant called Strobilanthes cusia, and discovered that Yangmingshan was a suitable environment for it. He then collaborated with a local farmer to grow these plants to be used for dyeing.

Lin introduces the basic steps of creating indigo dye. “The first step is to soak leaves in water to release the chemical compound, indican. This in turn combines with another chemical compound, indoxyl, to become what we know as indigo,” he says.

“This whole process requires oxygen to be blown into the water, which we call ‘bluing,’” he goes on. “Then, lime is added to form a bluish clay. The blue clay has to be dissolved in water to become ‘indigo white’ before it can be used for dyeing cloth and paper.”

This complex process inspired Lin to search for a natural yet easier approach to extract the blue dye, so he began experimenting with different materials like plum wine, Yakult yogurt, and baking yeast, finding they were all great for making indigo. “Actually, the best and most natural way is by using hot spring water from Yangmingshan. It’s one of the most efficient ways of creating blue clay,” Lin proudly shares his finding.

Through his own experiments and research, Lin hopes to further develop local education at the junior high school level so that students can use materials available at home to create their own indigo dye, thereby also enhancing their knowledge of local ingredients and cultural heritage.

Experiments Sprouted from Personal Interests

Lin is very skilled at transferring his hobbies into research projects. He tells us that he was a flute player back in college, and even performed on TV shows. Later, he combined the concepts of flute playing with the knowledge of gaseous substances to work on a method of analyzing blood glucose using gas concentration. “My hope is that there will be opportunities in the future to identify potential diabetes in patients just by breathing into an instrument,” he says.

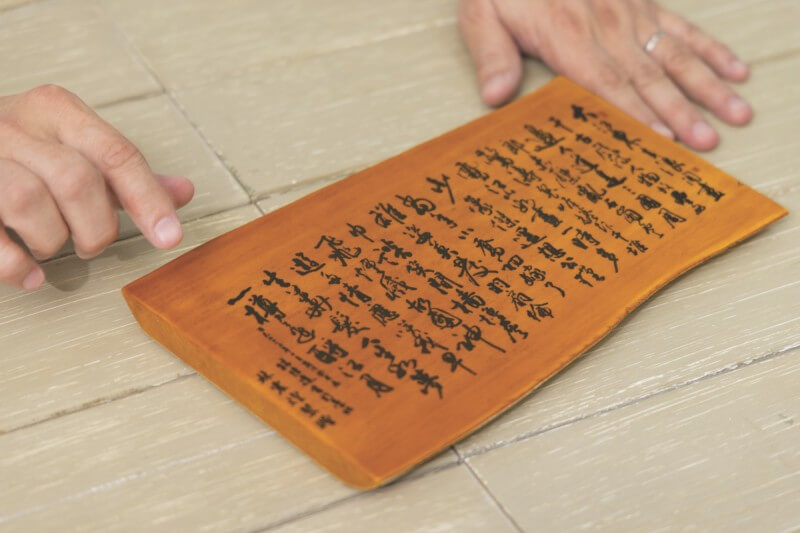

Recently Lin began taking up calligraphy, thinking about the utility of brushes and how they might be useful for discerning the metabolic rate of the human body. “I initiated a research project that involves using writing brushes to test metabolism,” says Lin. He asked participants to drink coffee and then rubbed their eyelids with brushes to transfer the metabolites. Afterward, he used a pulse of electricity to collect the ions from the brushes. “By determining the ionic concentration, we can then analyze the body’s metabolic rate,” he maintains. (Read also: More Than Calligraphy: Hsu Yung-Chin, a Calligrapher Combining Old and New)

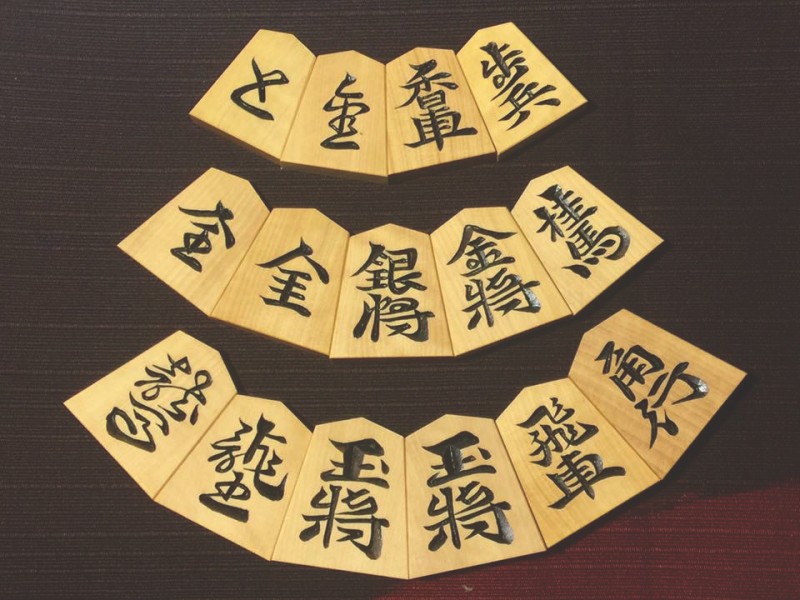

As if all of that wasn’t already enough to keep the professor busy, he has added yet another portion to his plate of late. “I also play chess at the Japanese Shogi League in Taipei twice a month,” he says, “But since chess pieces are so expensive, I’m learning how to make them myself, including the calligraphy, laser engraving, and paint,” he chuckles.

Lin is forever astounding us by coming up with new possibilities for scientific experiments that stem from his own life and interests, and combining his love of chemistry with music and art to create a more diversified life for visitors and locals alike in Taipei.

Author Catherine Shih

Photographer Yenyi Lin, Taiwan Scene, Cheng-Huang Lin

This article is reproduced under the permission of TAIPEI. Original content can be found on the website of Taipei Travel Net (www.travel.taipei/en).

Comments are closed.