Author Chris van Laak

Photographer Chris van Laak

People who’ve visited Taiwan (or those who, like me, live here) have probably all been asked this question by an “outsider” before: “What is so great about Taiwan?”

Once a friend visiting from abroad phrased the question a little differently—“What is Taiwan’s gift to the world?”—and it made me ponder the answer a bit longer than usual. What I eventually came up with was this:

“Taiwan’s gift to the world is the cinema of Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Edward Yang.”

Hou Hsiao-Hsien won the "Best Taiwanese Filmmaker of the Year Award" at the 42nd Golden Horse Awards. (Photo・Taiwan Culture Memory Bank)

Edward Yang, winner of the 31st Golden Horse "Best Original Screenplay Award. (Photo・Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank)

To me, the movies of the two eminent directors are a gateway to a Taiwan before my time, especially Hou’s A City of Sadness(悲情城市) and Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day(牯嶺街少年殺人事件). Although those movies offer veritable history lessons about Taiwan in the aftermath of becoming the Republic of China, they also convey something that history books cannot convey—they bring back to life the vibe of a bygone era that is just as essential to understanding modern-day Taiwan.

However, the world had to wait until the time was ripe for movies about painful events that had been all but taboo in the first decades of post-Chinese Civil War Taiwan.

Travel Back in Time

A City of Sadness was released in 1989, and Hou had to deal with the fact that what he sought to depict lay over 40 years in the past: That is, the tumultuous year 1947 when tensions between Taiwanese who had been living there since long before the war and those who recently arrived with the ROC government, but primarily the government itself, brought Taiwan to the cusp of another civil war.

For A Brighter Summer Day, released in 1991, Yang only had to “travel back” to 1960, when his movie about youth gangs in Taipei takes place. But the challenge to find scenery that could substitute for a Taiwan of the past was similar for both directors—and both came up with different solutions.

Hou Hsiao-Hsien‘s Jiufen

Hou chose Jiufen(九份), then a former mining town that had not yet seen much of a tourism boom, as the backdrop of his movie about the 228 Incident (二二八事件), an island-wide uprising against the nonperforming government that was suppressed violently.

![Jiufen overlooks the Pacific from a ridge on Taiwan's northeast coast.

(Photo・Chris Van Laak)

[in the movie: around 00:24:05]](https://taiwan-scene.com/app/uploads/2024/02/H1b-1160x773.jpeg)

To Hou, focusing on relatively “small” events in the periphery of world history served at least two purposes. It allowed him to fictionalize the underlying dynamic of the conflict, such as warring identities and the paranoia emanating from a state apparatus that was still in a wartime mindset. Like this, the fighting elsewhere in Taiwan didn’t get in the way of his subtle storytelling.

The suspiciously idyllic setting is therefore not incidental, nor is the film’s main character: Lin Wen-ching (林文清), played by the soon-to-be Hong Kong superstar Tony Leung (梁朝偉), is the deaf-mute youngest of four sons of a family that is drawn into the maelstrom of history. His distance to the conflict, in terms of his hometown’s remote location, but also his distance to the languages linked to the warring identities, allows him to—spoiler alert—withstand the forces of history the longest among his brothers.

However, Hou also chose Jiufen because its vibe came closest to that of the past—and in a way it still does. Sitting on a ridge about 300m above the coast, Jiufen’s vista of the Pacific gives it a timeless charm, as do the narrow stairways that connect its bustling streets on which many scenes of A City of Sadness were filmed. However, Jiufen is no longer remote, as buses that run as frequently as every 10 minutes ensure that visitors have easy access from Taipei.

![(Photo・Jason Wijaya Tanki) [in the movie: around 00:34:00]](https://taiwan-scene.com/app/uploads/2024/02/IMG_7163-1160x773.jpg)

In contrast to modern-day Jiufen, A City of Sadness implies that its characters have to undertake an arduous train journey if they need to travel to Taipei, via the Shen’ao Line(深澳線) that until 1989 had its terminus by the ocean near Jinguashi(金瓜石). Upon return, they take a dirt road up the hill—walking or being carried in a sedan chair. The scenery provides the movie with some of its most iconic shots.

Klook.comEdward Yang’s “Taipei”

Edward Yang found himself bound to his location when filming A Brighter Summer Day. His four-hour epic is based on the real story of a Jianguo High School (建國中學) student who killed his girlfriend in 1960, and it draws a kaleidoscopic sociogram of teenagers in a Taipei fraught with social tension. Estranged from their families’ social roots in China, their lives are as much defined by innocent experimentation with a newly arrived Western culture (as the English title, inspired by an Elvis song, implies) as by abhorrent violence, culminating in the murder that the Chinese title (牯嶺街少年殺人事件, “Youth Homicide Incident on Guling Street”) insinuates.

Yang once told British writer Tony Rayns that he doesn’t find it interesting “when a bad guy kills someone or when a good guy does something good; it gets interesting only when a good guy does bad things or vice versa.” One of the great achievements of A Brighter Summer Day is—spoiler alert—that the cold-blooded, senseless murder committed by Si’r, the film’s anguished, but certainly not “bad” 14-year-old protagonist, seems inevitable amid the social circumstances of his time. The film conveys a sense that somebody had to snap, and unfortunately, but inevitably, it was this kid.

The movie largely takes place in a middle-class neighborhood south of Taipei’s Guting MRT station. The area had been developed during the Japanese colonial period, and in 1960 it still featured many Japanese-style single-family homes. Many civil servants lived in the area, most of whom had come to Taiwan when the ROC government retreated from China.

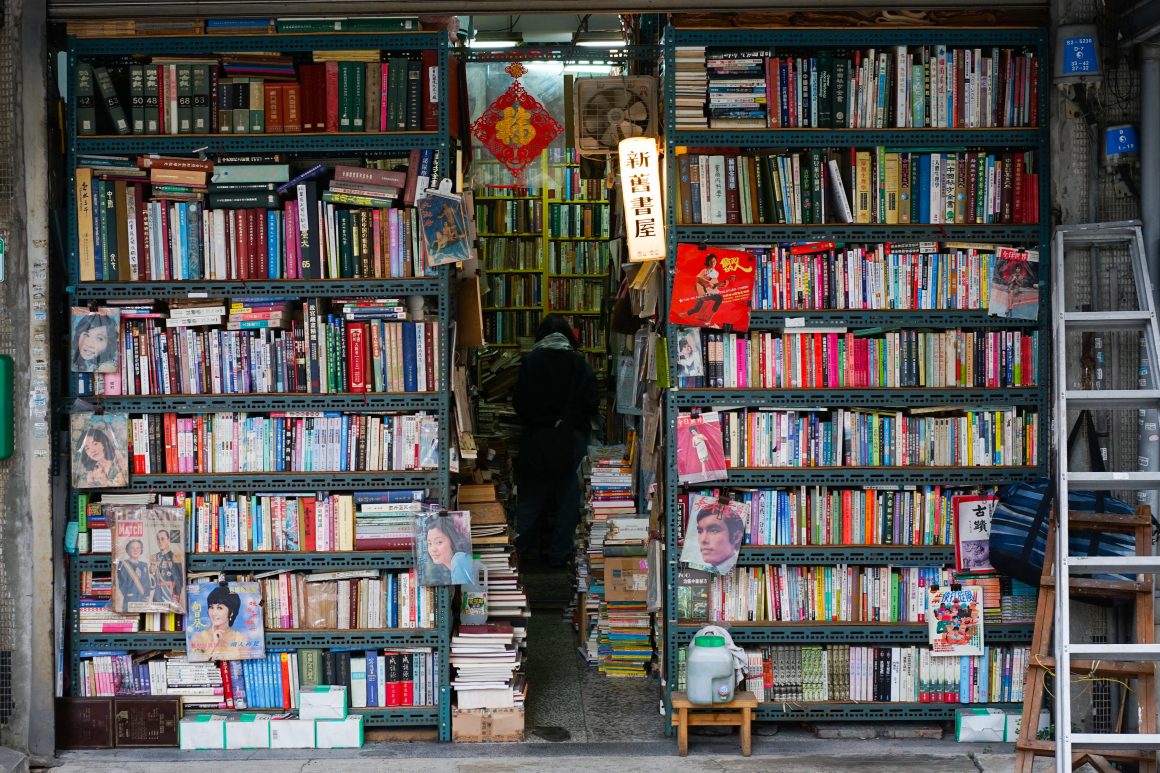

![Guling Street used to feature many used book shops and street stalls catering to students at Jianguo High School; little of the vibe of A Brighter Summer Day remains.[in the movie: 00:59:50]](https://taiwan-scene.com/app/uploads/2024/02/Y3c-1160x773.jpeg)

In Yang’s movie, all details play a role in the identity conflict; they are essential to his storytelling, but some of them were no longer visible in Taipei. As Taiwan’s capital had seen many Japanese structures being dismantled, especially such mundane ones as family homes, Yang had to look elsewhere: In Pingtung, as well as in the former mining town of Jinguashi, right next to where Hou filmed A City of Sadness.

Jinguashi features a cluster of Japanese-style buildings that once housed employees of the Taiwan Kogyo mining company (and now house, among other things, the New Taipei City Gold Museum). At the time when A Brighter Summer Day was filmed though, they were scheduled to be torn down to make way for an amusement park. That plan—luckily, in my opinion—did not materialize, but it gave Yang the chance to use them as a film set in the interim.

A changing political climate

The houses are still there, and some have been restored and are now open to the public, unfortunately not those where Yang filmed the indoor scenes of his movie though.

The local government’s decision to keep them likely had nothing to do with Yang’s movie, at least not directly.

However, A Brighter Summer Day and A City of Sadness were made possible not just by the genius of two great directors, but also by a change in Taiwan’s political climate. The movies were released at a time when Taiwan began to face its past more openly, including episodes that caused much suffering to Taiwanese. Instead of dismantling its history, it began to dismantle the false narrative of a harmonious past and reluctantly began to cherish the episodes that made it what it is today.