Author Chris van Laak

Photographer Amnesty International, frontline defenders.org

Editor Chih Yi Chen

Postcards are the ultimate heritage medium. Fewer and fewer people write them, as social media is far more efficient in letting friends and family know what life is like on the other side of the world. Because it’s so rare to receive a postcard these days, I always feel thrilled when I do find one in my postbox from a faraway place.

However, unexpected postcards can also arouse very different emotions, especially if you receive many at once.

(Photo・frontline defenders.org)

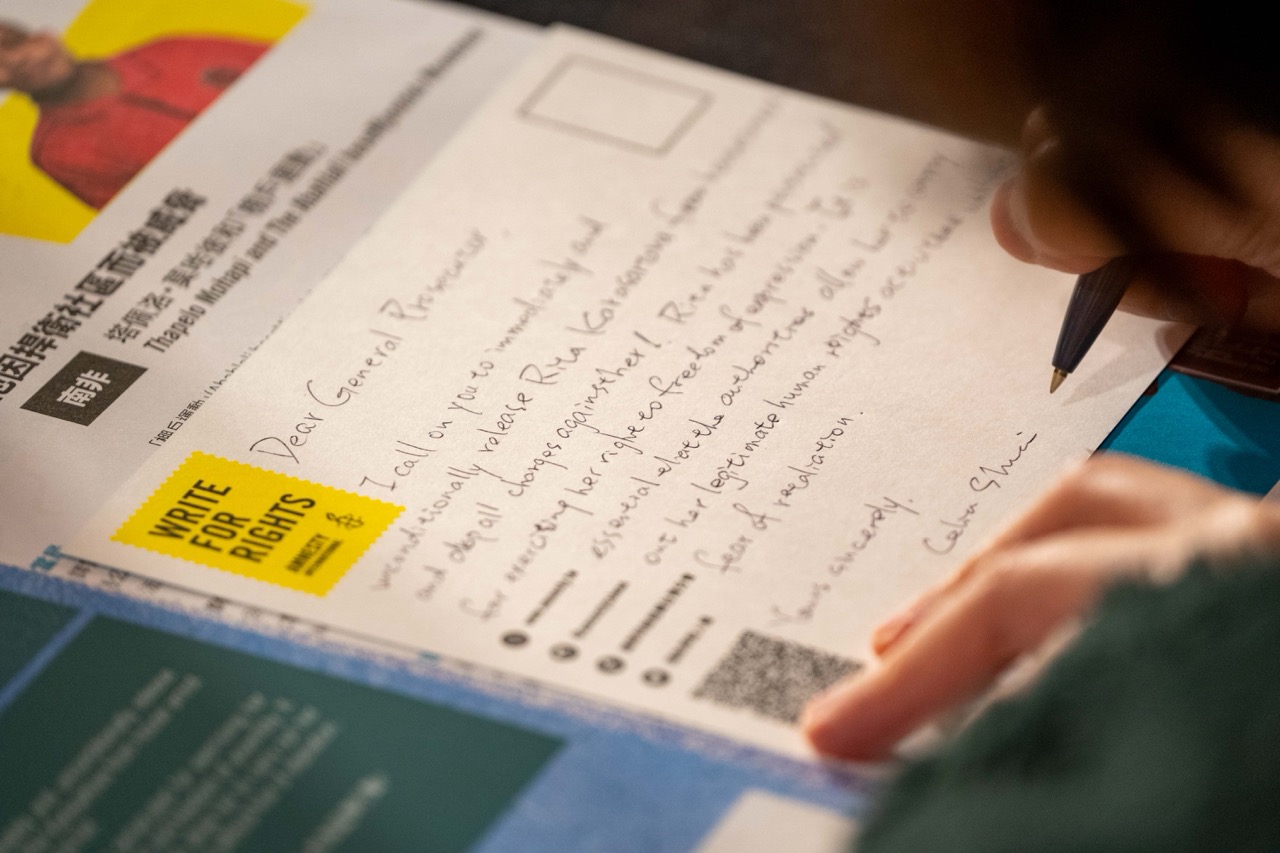

When, for example, the Prosecutor General’s Office of Kyrgyzstan last year received about 400,000 handwritten postcards demanding the release of Rita Karasartova, a human rights advocate who had been imprisoned for “trying to overthrow the government,” the office was overwhelmed. A few months later, it dropped the charges and begrudgingly acknowledged that Karasartova had done nothing wrong when she organized a protest over water usage rights—something that even the restrictive legal system in the Central Asian country must allow.

A few hundred of the postcards written on behalf of Karasartova were sent from Taipei; they were written by ordinary Taiwanese and foreigners who participated in Amnesty International’s annual Write for Rights event, which is set to take place again this weekend in Taipei. It will also be held in Taichung and Kaohsiung later this month.

How it started; how it’s going

Write for Rights is a global event held each year around Human Rights Day on Dec. 10. It started modestly, with a self-organized group of Polish Amnesty International members gathering in Warsaw in 2001 to write “truth to power” and demand the release of political prisoners. During their 24-hour marathon, they wrote over 2,000 postcards. The headquarters of the global human rights organization was so impressed by its members’ dedication that it picked up the idea and promoted it to sections in other countries. In Taiwan, the first Write for Rights was held a year later, as an informal event involving Amnesty staff and their friends.

The event has grown enormously in scale, but the way it operates remains the same.

When I asked Eeling Chiu (邱伊翎), the executive director of Amnesty’s Taiwan section, whether writing postcards is still as effective as it was back in the day, she pointed out that the event leads to political prisoners being released every year, most recently Rita Karasartova.

Its “old-fashionedness” is probably the biggest strength of the event. By focusing on a medium that’s hardly ever used nowadays, it overwhelms the recipient institutions and forces them to react. Quite obviously, having 400,000 postcards delivered to your postbox carries more weight than, for example, receiving the information that the same number of people have e-signed a critical petition.

How does it work?

The Amnesty International Global Headquarters in London usually selects 10 cases from among its global campaigns to be highlighted at Write for Rights.

At the event sites, local teams provide all that is needed: pencils, postcards and an entertainment program including MCs and music, sometimes played live, but also detailed information about each of the cases in the event’s local language. Write for Rights being a global event, information on the cases can be found online in multiple languages, ensuring that everybody can participate in any language.

The cases come from around the world and showcase the diversity of Amnesty’s work. Just like all other country sections, Amnesty International Taiwan can propose cases for the event. It does so every year, but the last time one of its cases was featured was in 2012, when participants wrote postcards demanding the release of death row inmate Chiou Ho-shun (邱和順).

Over a decade later, Amnesty’s demand has not been met. However, it continues to campaign tirelessly on behalf of Chiou, who was sentenced to death in 1989 after confessing—under what Amnesty calls torture—to the murder of an insurance saleswoman in Miaoli two years earlier. The case is shrouded in controversy to this day. Chiou retracted his confession almost immediately, but with sentiment in Taiwan remaining pro-death penalty, Amnesty’s campaigning for his release, as well as the abolishment of capital punishment altogether, have apparently not built enough pressure yet.

“Some things take a lot of time,” Eeling Chiu said. “A majority of countries around the world have already abolished the death penalty, but many in Asia still sentence convicts to death. We hope Taiwan can be a leader in Asia and play a big role in human rights in the region.”

Amnesty’s work in Taiwan

Aside from the abolition of the death penalty, Amnesty’s work in Taiwan also focuses on the rights of minorities. Here the focus is less on individual cases of grave injustice, but on providing critical expertise to the government and engaging in long-term conversations with all stakeholders that might one day bring about change.

For example, Amnesty is continuing to urge the government to incorporate additional UN treaties into Taiwanese law, as well as human rights clauses in a proposed trade agreement with the US.

During our interview, Chiu also highlighted Amnesty’s advocacy for the inclusion of cross-national same-sex couples in Taiwan’s marriage equality law, including couples involving a partner from China.

She also mentioned migrant workers’ rights and the rights of Indigenous Taiwanese, who, in part thanks to Amnesty’s campaigning, can now register at district offices under their real names—names in tribal languages written in Latin letters, instead of their Chinese transliterations, as was previously required.

Strong in Taiwan

Amnesty is one of the biggest global human rights NGOs. Even those who don’t know any specific campaigns will know the organization’s fundraising activities, often conducted by volunteers eager to collect cash commitments from passers-by in front of MRT stations. It’s unfortunate that Amnesty sometimes comes across as a bit pushy and that its communication strategy seems focused on enticing donors.

Grassroots fundraising is a necessity though, said Chiu, as Amnesty relies on small-scale donors who, in contrast to billionaire philanthropists and corporate sponsors, will not try to impose their own agendas on the organization.

Amnesty has to defend its independence as it adheres to principles of internal democracy, Chiu said, especially in difficult times.

“In general, human rights NGOs are facing a shrinking space,” she said, adding that the organization’s China section has to operate from outside the country, while its offices in Hong Kong and India had to close recently, under pressure from the respective governments.

“Having a strong presence in Taiwan is so important,” she said. “Taiwan plays an important role in the global human rights space, as a strong voice in the region and as a country that’s positioned between the Global North and Global South.”

Part of the Taiwan section’s efforts simply focus on ensuring that the country is being heard at all.

For example, Taiwanese members of the Amnesty delegation at the recent COP climate summit would have had to sign up as being from the People’s Republic of China, she said.

“We Taiwanese know these are not just political problems between states, but also human rights problems,” she said, adding that Amnesty officials from other countries are often unaware of the problems their Taiwanese colleagues are facing.

“We are working on changing that,” she said.