Author/ Photographer: Trevor Padgett

Editor: Julien Huang

Popular for its night markets, beaches, and year-round good weather, the Hengchun Peninsula is justifiably a top destination in Taiwan. However, this southern region of Taiwan is also home to a globally rare ‘uplifted coral reef’, ancient reefs that have been thrust out of the ocean and taken over by forest. A journey to Hengchun is not complete without experiencing these terrestrialized reefs – from fossils to cliffs to caves.

Approaching the peninsula: a rocky wave

Traveling south along Highway 26 towards the Hengchun Peninsula is one of Taiwan’s most impressive stretches of road. And as you follow the road south, with emerald-green forests on one side of you and a shimmering opalescent ocean on the other, one topographical formation in the distance bares unmistakable resemblance to a fossilized wave. Jutting out into the Pacific Ocean, this wave of rock has a remarkable story to tell of ancient coral and tremendous time.

Guanshan: A coral wave with a view

This is Guanshan. From this distance the western flank swoops gently out of the valley, stretching upwards until it crests in a thin plateau more than 150 m above sea level, before dauntingly ending in a precipitous sheer cliff that drops to meet the ocean.

One of the most visited places in the peninsula, standing at its plateau and looking almost due east you are greeted with an unobstructed 180◦ view of the ocean and open blue sky. And in the late afternoon, Guanshan offers visitors probably the best sunset views in Taiwan. Besieged by visitors each afternoon, the ridge erupts in life with eager eyes and cameras awaiting the celestial art painted by the setting sun.

While sunset and its panoramic grandeur draws people in, unbeknownst to them while they watch each day end is the secret hidden below their feet: the rocky wave on which they stand is actually a 500,000 year old coral reef, and ancient marine ecosystem that has been thrust out of the ocean and given to the land. This remarkable and globally rare geological formation is called an ‘uplifted coral reef’, a unique karst ecosystem that is spectacular in both its beauty and natural history.

Leaving the ocean: a coral reef of trees

Coral reefs ecosystems are made of the coral animals themselves – coral polyps excreting calcium carbonate to build mineral ‘houses’, known as corallites, that grow en mass and form the reef structure itself, giving homes and breeding grounds to inexplicable diversity of fishes, shrimps, mollusks, cephalopods, snakes, urchins, anemones, and countless other species. There are over 800 described species of coral globally, and more than half of those can today be found in Taiwan’s waters.

And it was that way hundreds of thousands of years ago, too. Many different species, for certain, than we see today, but the reef and the ecosystem would have been just as enigmatic and otherworldly as today’s. But sometime in the Pleistocene – the same time that mammoths populated steppe ecosystems and early humans roamed Africa and Eurasia – tectonic forces that helped build Taiwan began pushing these coral reefs out of the water. And kept pushing. Today they are still rising at a rate of approximately 1-2 mm/yr.

As these marine reefs were pushed upwards, imperceptible over the lifespan of, say, an individual fish or coral, but unmistakable over larger swathes of time, the ecosystem began to die. As the reef was pushed up the water became shallower, hotter, and eventually absent. Eventually the reef was hoisted out of the water, hundreds of meters into the sky, forever leaving the marine and entering the terrestrial. Although these terrestrialized ancient coral reefs have been taken over by trees and lianas and ferns and lichen and fungi and beetles and monkeys and civets and mongoose and butterflies and deer … they still maintain the unmistakable beauty of a coral reef, building a stunning ecosystem with a clear memory of its marine ancestry.

Banana Bay: Where the reef leaves the sea

A journey through the Hengchun Peninsula’s uplifted coral reefs should start where it begins: where the reef leaves the sea. There is no better place to see this than at Banana Bay, a rocky and treacherous world of fringing coral reef with its fossil-rich but sharp-edged now-exposed rock guarding the coastline. But, luckily, to appreciate this bay we don’t need to wander far: surrounding us is the coastal forest, a protected remnant of salt-tolerant trees with floating fruit, evolved to disperse their seeds via ocean currents; in the trees and burrowing at your feet are more than 35 species of land crabs, combining to give this bay the highest diversity of land crabs in the world; in front of you within the rocky patches of the fringing reef are pools perfect for swimming; past the break are vibrant living coral reefs.

Glancing down the coast and then out to sea, the world is saturated by coral. Thriving in the water, fringing the barren coastline, and blanketed with forest. And it is here, at this coastline, that we can see the geological process of coral reef uplift happening. We see the stages, not the movement. But the landscape is a forensic story of a reef that has – and is still – moved from sea to land.

Sheding Nature Park: Coralline cliffs of fossils

Sheding Nature Park boasts accessible walking trails, exceptional ocean views, glowing mushrooms, sika deer, endemic snails, tree-dwelling crabs, native snakes, and a great diversity of butterflies and beetles. It is also – during the autumn migration season – a place where tens of thousands of raptors flood the skies every day looking for a rest stop on their way south. It is, from season to season and morning to night, a nature lovers paradise. And, hidden beneath all this biological splendor, is a coral reef.

And much like Guanshan, this coral reef is unseen by most. This is understandable. The coral rock has been heavily worn away by the rains and winds of time, and a thick layer of soil hides much of the tell-tale coral landscape. However, there are clues.

Walking into the park we are quickly greeted by massive walls of rock, split by thin crevices these geological monoliths protrude into the yawning blue sky. Capped with clinging fig trees and scandent vines, painted with purples and yellows of vines and herbaceous plants, these exposed rocks not only offer picturesque beauty but also a secret to their ancestry: fossils.

The walls of these rocks are an art gallery of time, their walls festooned with fossils that to even an untrained eye are unmistakably coral. Large coralline images follow you as you walk through the valleys, crevices, plains, and clifftops; some large with massive bodies preserved intact, others small and fragmented. We do not need to know the names of species or the ages of their existence to appreciate the meaning they share: this used to be under water; I came from the ocean.

Kenting National Forest Recreation Area: Coral forests and caves of time

The Kenting National Forest Recreation Area puts its coral reef ancestry on vivid display, and a network of trails offers you options to wander through the vast reef-turned-forest. Along the trails the ancient coral geology is humbling: multi-story tall cliffs, sweeping rocky valleys, plateaus punctuated by coral outcrops, and cracks in massive coral rock slabs big enough to enter. Though today this coral landscape is covered by a forest of karst-adapted tropical plants, it is unavoidable to imagine the marine past. Where today’s fig trees cling to cliffs, sharks and rays used to float; where ferns and fungi hide in cracks, urchins and mollusks used to live; where sinuous roots crawl through soil and wrap around exposed rock, coral and fish used to thrive. Stop along the trail – anywhere – and gaze up, imagining these marine scenes; though it has now been taken over by time and terrestrial life, it is still a coral reef in spirit.

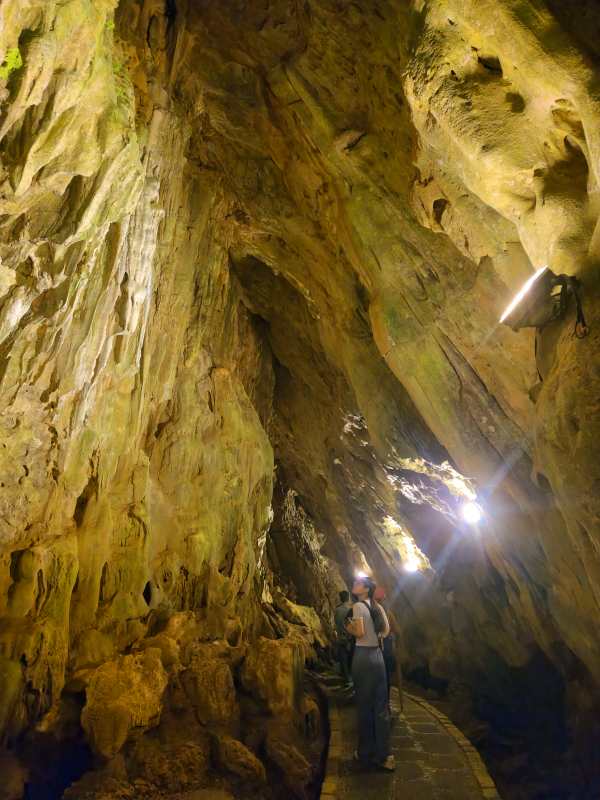

The coral reef – specifically, the soft calcareous rock that the once-living coral built over millennia – also gives us geological curiosities. Walking deeper into the forest, following the trail past thick hanging lianas and buttress-rooted trees, moving through an eerie echo of owls calling and macaques chattering, you eventually reach a small crack in the reef. Well, it was a crack: over time and many countless rainy seasons the crack became a cave – Fairy Cave, to be specific. Acidic rainwater infiltrating the crack dissolved the carbonate rock, eventually chemically eroding the body of rock inside and leaving behind a vast, empty chamber. The memory of this process remains not just in the massive chamber itself but also in the mineralized crystalline walls, stalactites, stalagmites, and curious mineralized forms decorating the cave roof, floor, and walls. The cave is not just immense and beautiful, it is a testament to the depth of time that built these coral reefs that we can now walk on and under.

Leaving the Reef

Exploring this uplifted coral reef is a truly enigmatic journey through time and space, beauty and biology. A thriving coral reef that was pushed out of the ocean and became a forest is easy to explore in Hengchun. Fossils tell the tales of the species that once lived. Crevices and caves expose the depth of time it took to build. And the coastline bears witness to the ever present reality that this – a tumultuous tectonic battle between reef and time – is unending. But beautiful. If you are interested in getting in the water and seeing the vibrant coral reefs of Kenting yourself, CT Divers (www.en.ctdiver.com) is a great place to start!