Author: Levarcy Chen

Photo: Levarcy Chen, Karenko Cooking Class

Editor: Julien Huang

Stepping off the train in Hualien, I’m greeted by crystalline mountain peaks framed against an impossibly blue sky. A taxi driver’s warm inquiry—”Where are you headed?”—launches us into easy conversation as we wind through narrow alleys toward Chongqing Traditional Market on the city’s southern, seaside edge. This welcoming spirit, I’ll soon learn, is woven into every aspect of the day ahead.

At the market entrance, Sofia Chiu waits beneath a fisherman’s hat, her wheat-toned skin and confident posture immediately distinguishing her from the regular market-goers. She spots me quickly—I’m clearly an out-of-town visitor, and she greets me with an easy warmth.

After brief introductions, we dive into today’s agenda: exploring the indigenous section of Chongqing Market.

Where Indigenous Traditions Meet Daily Life

Within Chongqing Market (重慶市場) lies a designated corridor reserved exclusively for indigenous vendors—a living archive of Taiwan’s indigenous food heritage. Taiwan is home to 16 officially recognized indigenous tribes, each with distinct languages, traditions, and culinary practices. The Amis (阿美族), Taiwan’s largest indigenous group, are particularly prominent in Hualien, known for their deep knowledge of wild edible plants and coastal resources. The Bunun people (布農族), traditionally mountain dwellers, are renowned for their hunting expertise and intimate relationship with Taiwan’s highlands. Though Hualien is home to multiple indigenous groups, the Amis people form the largest community here, and their agricultural wisdom dominates the market’s offerings.

Sofia’s market introduction focuses less on tribal distinctions and more on the overarching philosophy that unites indigenous food culture: eat what nature provides today. This isn’t simply about sourcing locally—it’s about moving in rhythm with the land’s natural cycles, taking only what’s given, and honoring each season’s bounty.

Our first stop introduces me to amla (餘甘子), small green fruits resembling oversized grapes. The vendor places several in my palm and explains their nutritional prowess with unhurried confidence. The eating experience itself is a journey: initial sourness gradually transforms into sweetness, a metaphor perhaps for patience rewarded. As she lists the fruit’s health benefits, I let the tartness linger while absorbing the market’s ambient sounds and rhythms.

Further down the corridor, Sofia gestures toward an elderly woman carefully sorting through herbs and vegetables. “She’s nearly one hundred years old,” Sofia says quietly, admiration evident in her voice. The Amis grandmother’s hands move with practiced precision, selecting wild greens with the kind of knowledge that comes from a lifetime of foraging. “The Amis are sometimes called ‘the grass-eating tribe,'” Sofia explains. “Their ability to identify edible wild plants is genetic—they have stomachs like lawnmowers.” Even as a Bunun person, Sofia admits she can’t match their botanical expertise.

The market tour becomes a parade of unfamiliar produce: gac fruit (木鱉果) with its spiky orange exterior reminiscent of a small durian, delicate wheel-shaped eggplants (車輪茄), and fuzzy-skinned persimmons (毛柿). At one stall processing snails, a vendor enthusiastically invites us to share a drink, insisting we meet up later that evening. Sofia leans in with a conspiratorial whisper: “They’ve already started their daytime party—maintaining a perfect level of tipsy.” I can’t help but laugh at the contrast between Hualien’s relaxed pace and the restrained formality of big city life.

This openness, however, isn’t universal. Many indigenous vendors maintain a quieter presence, going about their daily routines with modest reserve. Yet when asked about their produce or offered a taste, none refuse. Instead, they respond with generous portions, worried you might not have enough—a warmth that transcends words.

From Ingredients to Kitchen

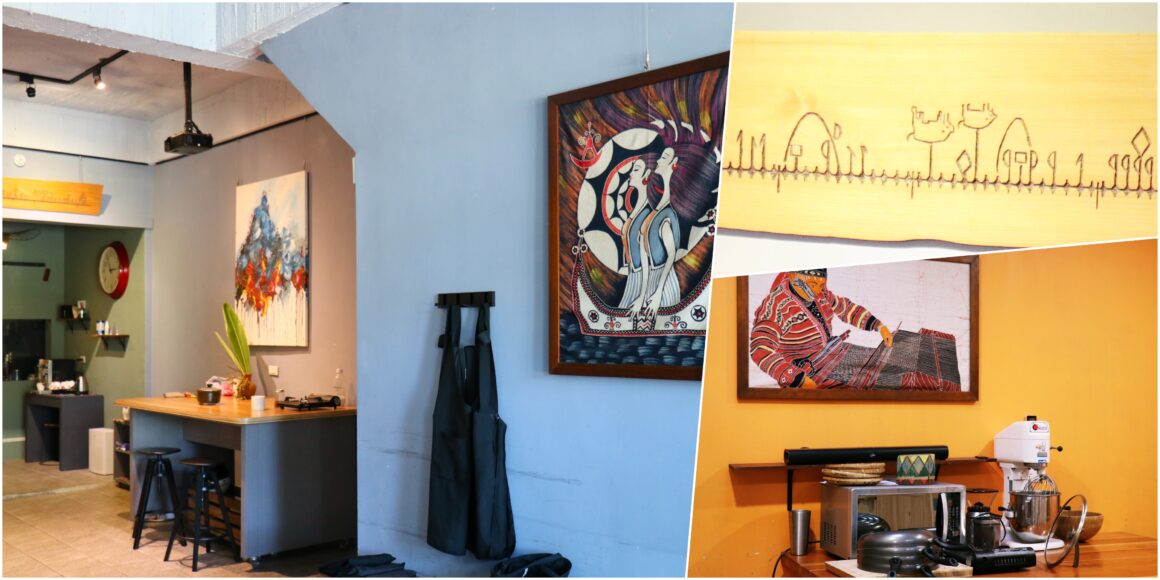

With our basket filled with indigenous specialties, common aromatics, and fresh meat, we drive along Hualien’s coast to Sofia’s cooking space. A member of the Bunun tribe who relocated to Hualien from the city, Sofia started Karenko Cooking Class out of a simple love for cooking and meeting people. Her fluent English allows her to welcome guests from around the world, sharing indigenous food culture across language barriers. She laughs as she explains the venue’s unexpected evolution: “I originally chose this location as a rest stop for digital nomads. But somehow, it turned into a cooking classroom instead.” Though teaching remains her side business, she treasures each guest who walks through her door.

I ask about the pandemic years—surely they were difficult? “Not really,” she says with surprising candor. “Domestic tourism actually kept us incredibly busy. It took a while before I finally got a break.” As we chat, Sofia moves fluidly through the space—donning an apron, shuttling ingredients from kitchen to workspace, offering drinks. “Coffee, tea, or maybe some of my homemade pomelo wine?”

A sudden movement catches my eye: a round, grey creature with enormous eyes peers from around the corner. The beautiful grey cat approaches with gentle curiosity, waiting patiently to be noticed before offering a friendly meow. For someone unaccustomed to cats seeking attention, this warm reception feels like a blessing—a perfect prelude to the cooking ahead.

Hands in the Work, Heart in the Process

We begin with rice, though not the everyday variety. Today’s base is glutinous rice mixed with red quinoa, destined to be wrapped in shell ginger leaves. Sofia demonstrates how to lightly toast the broad leaves over flame, and I watch water vapor escape rapidly from their surface pores. The toasting softens the leaves while releasing their distinctive aroma—ginger-like but sweeter—that soon fills the entire room.

Sofia guides my hands through folding the leaf into a small pouch, filling it with the rice mixture, then using the leaf’s own stem as natural twine to seal the bundle. These charming packets go into the rice cooker for an hour of steaming. While modern indigenous cooking often uses rice as filling, Sofia notes that traditionally, anything could be wrapped inside—a testament to the cuisine’s adaptability.

Next comes the gac fruit and pork rib soup. Since I’m cooking solo today, Sofia alternates between instructing and prepping, ensuring I can both participate and document each moment. Cutting into the gac fruit reveals pumpkin-like flesh housing a citrus-textured interior. Nervous about wasting this unfamiliar ingredient, I work slowly and carefully. Sofia and I fall into easy conversation—swapping life stories, discussing relationships, sharing the kind of comfortable gossip that happens between friends. It feels less like a cooking class and more like visiting an old friend’s kitchen.

As ingredients came together, Sofia helped sear the pork ribs with garlic and ginger before adding water and gac fruit to a clay pot, which we set to simmer gently. Then we move to my favorite part: grinding maqaw (also known as Mountain Litsea) in a mortar and pestle. These small black seeds, called mountain pepper by some, have earned international recognition as possessing a “sexy” flavor profile. Like a perfumer’s creation, maqaw evolves on the palate—opening with ginger and lemon notes, transitioning to lemongrass, finishing with a peppery kick. Combined with the shell ginger leaves steaming nearby, the air becomes a feast in itself, anticipation building with every aromatic layer.

I massage the ground maqaw into chicken thighs, leaving them to marinate while we move to the rear kitchen. Two large skillets heat simultaneously as Sofia adds vegetables in a rainbow of colors—red, green, yellow. “I like incorporating different colored vegetables,” she explains. “It makes the dish beautiful and ensures balanced nutrition.” Finally, the marinated chicken hits a hot pan, skin-side down. As the Maillard reaction works its magic, transforming the skin golden and crispy, our cooking duties officially conclude.

We also prepare a coastal specialty: seaweed salad brightened with indigenous chili sauce, its particular heat adding another dimension of flavor that coastal areas have perfected over generations.

The Ritual of Eating

Each dish finds its place in elegant serving bowls, and suddenly, a complete feast emerges—one created by my own hands. Sofia urges me to eat while it’s hot, busying herself with cleaning the workspace and stovetop. After documenting the spread properly, I approach the meal with something like reverence.

Every bite carries layers of meaning: indigenous history, generations of culinary wisdom, and the ingenuity born from living closely with the land. When Sofia emerges from the kitchen and asks how it tastes, I’m too absorbed in eating to respond verbally. My enthusiasm, however, speaks volumes.

More Than a Cooking Class

From that first glimpse of mountains upon arriving at the station, through the preserved indigenous culture coexisting harmoniously within the market, to physically engaging with ancestral knowledge and wisdom, the experience offered exactly what my city-rushed soul needed. A leisurely morning. Unhurried shopping. Meandering conversation while cooking. Slow, mindful eating.

This wasn’t simply about learning recipes—it was about remembering that life can be savored, that food connects us to place and history, and that sometimes the best medicine for modern exhaustion is returning to fundamental rhythms: gathering, preparing, sharing, enjoying.

Karenko Cooking Class

🔗 Link: Facebook

⏳ Duration: 3 hours (cooking and dining only) / 4 hours (including market tour)

💰 Fee: NTD$1,800~NTD$2,200 / person

🕰️ Operating Hours: 09:30-13:30 & 15:30-1830 2 sessions

⚠️ A 2-day advance appointment is a must.

📍 Location: No. 7-1, Minquan Rd, Hualien City, Hualien County, 970

📌 Note: Advanced booking required. Cancellation upon the day of arrival with no refund.

For the most current information and reservations, visit their website or contact directly through their social media channels.