WORDS BY Catherine Shin

PHOTOS BY Samil Kuo, Taiwan Acrobatic Troupe

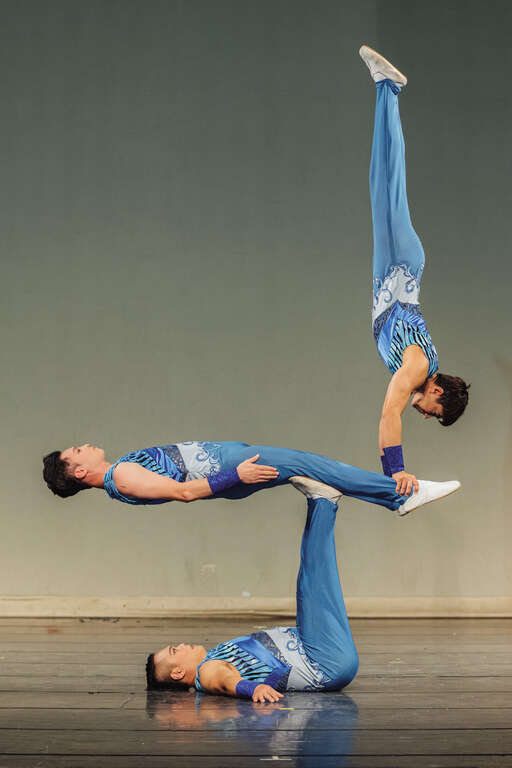

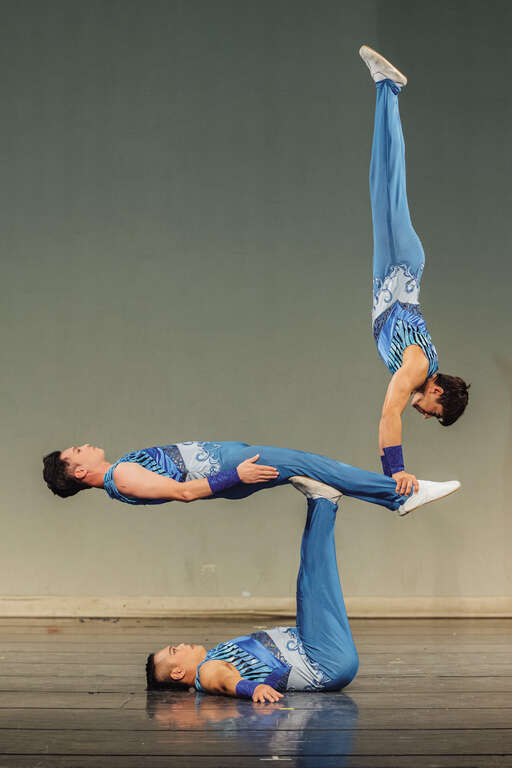

Unique, jaw-dropping performances, such as balancing on scattered ladder poles (散梯竿, san tigan), high poles (高竿, gao gan), living bicycle pyramids (飛車羅漢, feiche luohan), and martial arts are just a few of the traditional folk acrobatics that have marveled and captured the eyes of foreign visitors for decades. TAIPEI has been given the amazing opportunity to sit down with Wang Tongyuan (王動員), Director of Taiwan Acrobatic Troupe (台灣特技團), Chang Ching-lan (張京嵐), Chair at the Department of Acrobatics (民俗技藝學系), National Taiwan College of Performing Arts (NTCPA, 國立台灣 戲曲學院) and Dr. Liu Chin-li (劉晉立), President of the NTCPA, to help our readers better understand the background and development of this traditional, yet ever-changing feature of Chinese culture. We hope to provide our audience a glimpse into the awe-inspiring world of traditional folk acrobatics and learn more about this multifaceted dimension of Taipei.

Q1: How can we define “traditional folk acrobatics”? And how are they different from juggling or western acrobatics?

Assoc Prof. Chang:

Actually, the terms “juggling,” “acrobatics” and “circus” that we hear all the time essentially carry the same meaning when referring to “traditional folk acrobatics.” The only difference is that a “circus” normally entails animals and a circus tent and is found mostly in western countries, while “traditional folk acrobatics” are rooted deep in Chinese history and use everyday household props found around the house such as plates, chairs, balls, bamboo sticks, and others.

Traditional folk acrobatics were born from everyday life in rural China during the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 A.D.) when it was still a mostly agriculture-driven society. Back then, acrobatics were their version of the modern street performances that we have today. Over time it grew and eventually made its way across the strait to Taiwan, with many families running their own performing groups such as the Chang family (張家班), Zhu family (朱家班), and many others. Later during the 1950s and ‘60s, it eventually found its way into hotels, theaters, and opera houses around Taiwan as popular showcases where the audience could wine and dine with traditional folk acrobatics as their main form of entertainment.

Q2: Where are traditional folk acrobatics usually performed? What is the difference between the past and the present?

Director Wang:

Well, I began learning traditional folk acrobatics nearly 40 years ago when I was just 10 years old back in the fourth grade. Back then, traditional folk acrobatics occurred in places like temples, squares, or other public areas of gathering. Beforehand, it was just a “showing off” of your skills, but nowadays, artistic elements such as dancing and acting have been included, taking the entire experience and performance to a whole new level. These visual elements allow traditional folk acrobatics to be appreciated on a scale never done before.

In terms of the evolution of its performers, in the past, many students who came to learn were from single parent households or from financially disadvantaged families. Even growing up, around 70 to 80 percent of my classmates were from orphanages or single-parent families. However, times are now changing. Many of the students we see nowadays come from wealthy families whose parents are busy working abroad elsewhere in China or other places. For these parents, it’s an easy decision to send their children to our school because we offer boarding, food, and rigorous training and education.

Q3: Are there any unique costumes, props, or makeup for traditional folk acrobatic performances?

Director Wang:

Every performance requires unique props that are catered specifically to you and your ability or skill. You can think of them as your second lifeline — similar to how a soldier might view his or her rifle during a war. It really is one of the most important aspects of performance. For example, in a featured act like stacking chairs, the chairs we use are not the average wooden chair that you’d find in a classroom or restaurant. It’s not that we can’t use those; we can. It’s just that we would have less guarantee of safety if we did. So, instead, we have customized chairs that are lighter and created with better balance in mind.

The same goes for even something as simple as juggling. The balls the artist chooses to use may be smaller in size due to the size of his or her palms, and vice versa. The act that I perform used to require long bamboo shoots, but they were too difficult to bring abroad or would sometimes dry up and crack. Therefore, we’ve switched to a new form of aluminum instead. Not only are they lighter in weight, but more importantly, they are safer.

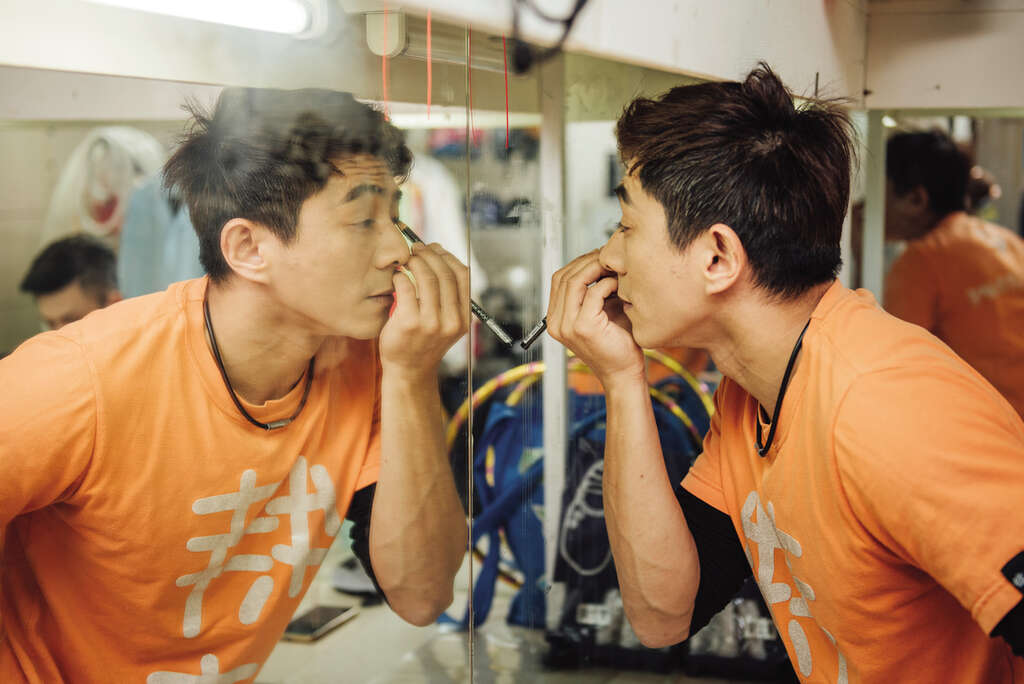

Generally, we are responsible for handling our own makeup and costume. Most costumes are tailor made to fit our specific skill set and cannot be sewn too tight or tailored using smooth material due to the risk of malfunctioning during performances. And we typically manage makeup on our own too, unless there is a special occasion on that day, in which case we sometimes hire a makeup artist for added assistance.

Q4: How long does it take to become a professional traditional folk acrobat?

Director Wang:

To develop a proper base and foundation for strong acrobatic skills, it requires constant practice every single day. In the beginning, when I first started learning, my teacher would often beat me with a stick or whip. And during the showers at the end of the day, the few of us boys would compare who had more whip marks on their back as marks of pride. To be honest, it was one of the quickest, most effective ways to learn back then (chuckles). Nowadays, we can’t do that anymore. That type of education and training isn’t allowed or possible.

The problem is that there is a real inherent danger involved in learning acrobatics. If you fall three stories and land on your arm, chances are you are going to break your arm or wrist. That has happened to us many times before, and each time, that performer is out for at least three to six months — which means a temporary replacement is needed, only adding to the cost. Nowadays, we can only stress the urgency of learning and allow students to face the consequences themselves. As performers, we cannot use safety nets or ropes, so it’s even more critical that our movements are correct and we have a solid base for training. Necessary movements like stretching your arms back or doing handstands are the most basic requirements in joining this form of acrobatics, and upon arrival, the teachers will help you discover and refine your own talents as you grow in your abilities.

Q5: What are some traditional folk acrobatic skills that are amazing? What is their background?

Assoc Prof. Chang:

Actually, one of the most iconic and easily recognizable traditional folk acrobatic skills is the famous che ling (扯鈴) or “diabolo” (the “Chinese yo-yo” as some call it), which was carried over from China. Originally made from wood and bamboo, it was called “扯” (che, meaning spinning/pulling) because of the movement the performer made every time, though nowadays they’re mostly made of plastic. With over a thousand years of history, it has become an integral part of early childhood Taiwanese education, with many diabolo classes starting as early as elementary school all the way up until college. Another iconic performance is the stacking of chairs or various balancing acts using ladders or poles. Like most other performances, they both originated from China and use objects from daily life as a props.

Q6: What is the most difficult traditional folk acrobatic move? Why?

Director Wang:

Actually, to be honest, every single acrobatic movement is challenging in its own way — even juggling. Without constant stability and movement, even balls could fall and hurt or hit someone in the head. Traditional folk acrobatics are no different in this way. However, something worth mentioning is that for group performances, it’s essential to have a sense of mutual understanding among your team members. And for individual performances, however, having a strong foundation of basic skills is absolutely necessary. At front and center stage of all this is obviously one’s acrobatic skills. Without these skills, it would just be another group of people dancing on stage.

Q7: Talk about the transformation and improvement of modern folk acrobatics, integration with world culture (such as how foreigners can experience and watch performances), and the future performance plans of the Taiwan Acrobatic Troupe.

President Dr. Liu:

Traditional folk acrobatics were mostly based on skills and usage of props, such as the diabolo or cycling, and required lots of patience and perseverance. But using this type of traditional performance, performers are left restricted by old-fashioned mindsets or ways of thinking. “The New Circus” or “新馬戲” (Xin maxi, meaning “new circus”) emerging from France in recent years has begun to change the way audiences experience and think about circuses. By using other elements such as lighting, 360-degree projection, dancing, acting, ballet, modern dance, gymnastics, or new props and costumes, we can introduce a new form of traditional folk acrobatics that speak to the audience on various levels. In fact, it even changes and pushes the boundaries of traditional folk acrobatics. For example, we can create the illusion of clouds or a forest that makes the background appear almost 3D-like for the audience and blends that backdrop in with traditional folk acrobatics. I believe that foreigners alike can appreciate this type of performance since it is not constricted by language barriers that you may normally get while watching the Peking opera, for instance.

For performance information,

check out https://www.facebook.com/TaiwanAcrobaticTroupe

Traditional Folk Acrobatics: Bringing Taipei to New Heights (CH/JP sub)

This article is reproduced under the permission of TAIPEI. Original content can be found at the website of Taipei Travel Net (www.travel.taipei/en).