Author Chris van Laak

Photographer Chris van Laak

When the athletes arrived at the start of the TAIPEI 101 Run Up 2024, early in the morning on May 4, they couldn’t even see the top of the building. Its upper floors, including the observation deck on the 91st, where the finish line would be, were shrouded in low hanging clouds.

“A bit crazy, wasn’t it?” Rudolf Reitberger asked his fellow Austrian tower runner Marlies Penker at the medal ceremony a few hours later. The event had just ended; Reitberger had just finished his sixth tower run at the iconic 508m-high skyscraper. His first was 19 years ago at the event’s maiden edition, where he had the honor of making the first-ever timed run up the 2,046 steps. Penker, a first-timer in Taipei who has over 20 Ironman Triathlons under her belt, had just clinched a superb 5th place.

“Crazy” is an overused term when it comes to niche sports that take a lot of dedication and stamina. But you should really be a bit crazy if you try to run up one of the highest buildings in the world as quickly as you can—especially if it is not just as a once-in-a-lifetime thing to explore your physical limit, but you do it again and again, year after year, in Taipei and at the other stops of the TowerRunning World Tour on four different continents.

The TAIPEI 101 Run Up is divided into two categories. One is for amateurs who are brave enough to take the challenge, and the other is for crazies of a different magnitude—the elite runners on the World Tour. This year, about 5,000 participants started in the amateur category, while the elite category comprised 74 starters—45 men and 29 women.

The pros got ready first, and as if the 2,046 steps weren’t tough enough, this year’s race came with an additional challenge. About 30 minutes after the last elite runner arrived on the 91st floor, a second, “sprint” round from the first to the 59th floor awaited them. In both rounds, they started at 30-second intervals, and their times were added up for the final result.

Seven seconds per floor

Valentina Belotti from Italy was the fastest woman, clocking in at 22 minutes, 29 seconds. Wai Ching Soh(蘇偉清) from Malaysia won in the men’s category in 18 minutes, 39 seconds. (For those who want to try to match his pace at home, that is about 7.5 seconds per floor.)

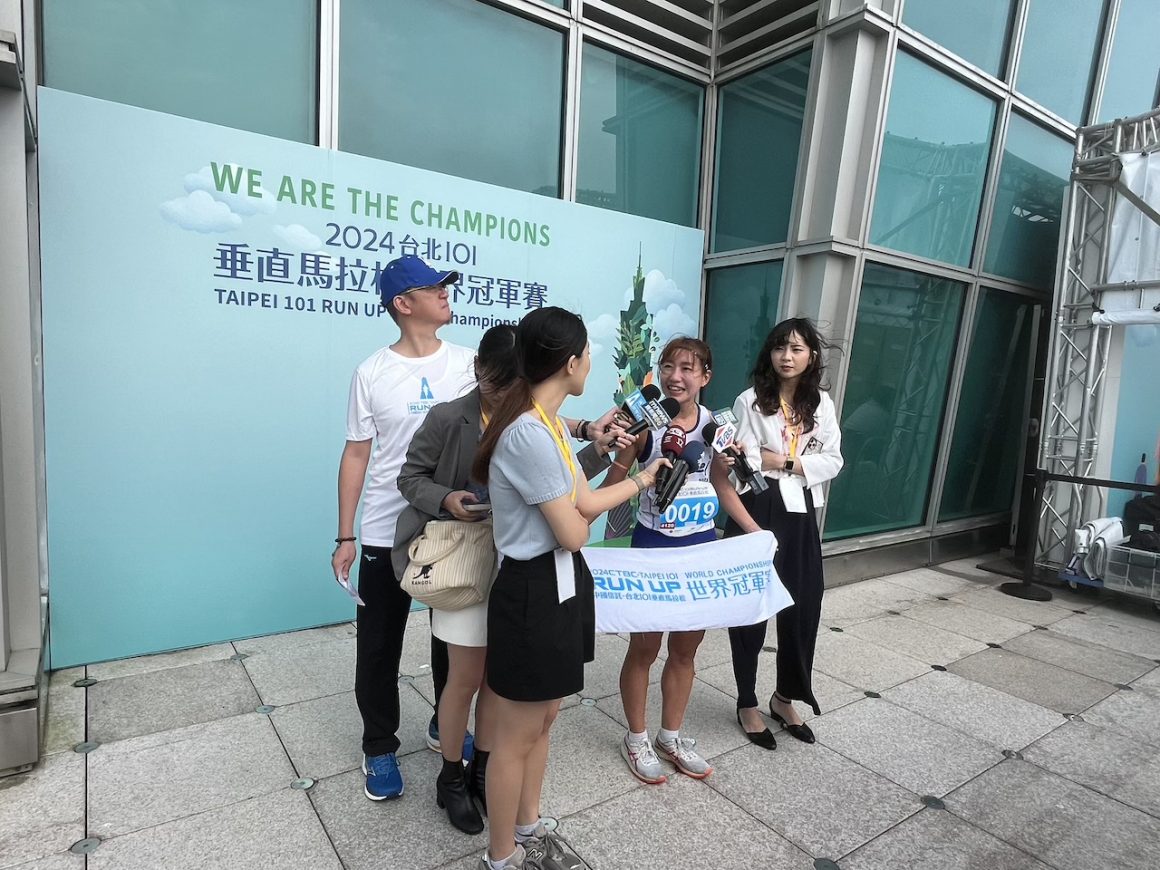

There are also some Taiwanese among the world elite. In the men’s category, Ching Chun Lo (羅清駿) was the fastest local hero, ranking 8th, while Jui Chuan Chao (趙瑞娟) finished 6th in the women’s category.

The fastest among the elite runners are usually younger athletes who specialize in the sport—full professionals in their 20s or 30s who dedicate their life to it. There is also a lot of diversity though; there are trial runners and triathletes, and the ones whose bodies defy the idea that youth trumps older age. Marlies Penker is in her early 50s for example, which shows that the challenge is not just about strong, youthful legs.

For example, Tower runners need a higher degree of control over their body than athletes in other sports. They have to perform the same succession of movements with a precision that even other endurance athletes—swimmers, runners, cyclists—are not necessarily capable of.

Rudolf Reitberger, who is also in his 50s, said he can no longer improve his personal best from back in the day, but one thing remains the same: Precisely every five floors he looks at his watch to check his pace. The difference between each five-story section should not be more than one second.

“If runners are too fast or too slow, they won’t be able to recover it, unlike in an ordinary marathon,” he said.

A special kind

Tower running is also a formidable mental challenge. In contrast to city marathons, for example, tower runners are alone while fighting their way up the narrow staircase. There are no landmarks that could help them structure their run, no people cheering along the way. If they meet another runner, it means they have either gained or lost 30 seconds on them; it usually means one of them is in trouble.

However, there is a great sense of community among the runners. This was most apparent at the finish line, where those who still had the stamina to keep it together helped those who were falling apart. There is a mutual understanding that they all excel at something that many outside their small circle would never want to try.

Why does a person get into tower running in the first place?

Silvester Gomboc from Slovenia, one of the few elite runners over 60, said every time he goes running, he wants to challenge himself. When he sees stairs, he sees a challenge, and ever since he has started running them, lesser challenges are no longer interesting.

Or in the words of Rudolf Reitberger, “You have to be a special kind of person to do this.”

One of the few runners who cited a reason that has nothing to do with seeking ever greater challenges is Minerva Hernandez from Mexico. She said running stairs is actually better for your knees than running on flat surfaces.

Her joints wouldn’t allow her to run a city marathon, she said, but after practicing spinning for many years, she gave the stairs a shot. She has never looked back.

Although there is a clear separation between elite and amateur runners at the TAIPEI 101 Run Up—there is for example no “sprint” round for amateurs—it is remarkable how far dedication alone can get you as a tower runner.

Many of the older elite runners don’t have the typical biography of a professional athlete, and many of them came to the sport relatively late.

“In no other sport would this be possible,” said Andrew Gage from the UK, who started tower running in his 40s on a whim, during a trip to New Zealand nine years ago.

Your next chance

The TAIPEI 101 Run Up is held every year. It is as well established on the World Tour as it is as an event for ordinary locals and visitors who want to give it a shot. At the end of the day, you have to try it at least once to see whether you are a person of that “special kind.”

A clear advantage of the amateurs is that they have more time to enjoy the run, as well as more time to relax and explore Taipei before and after the event.

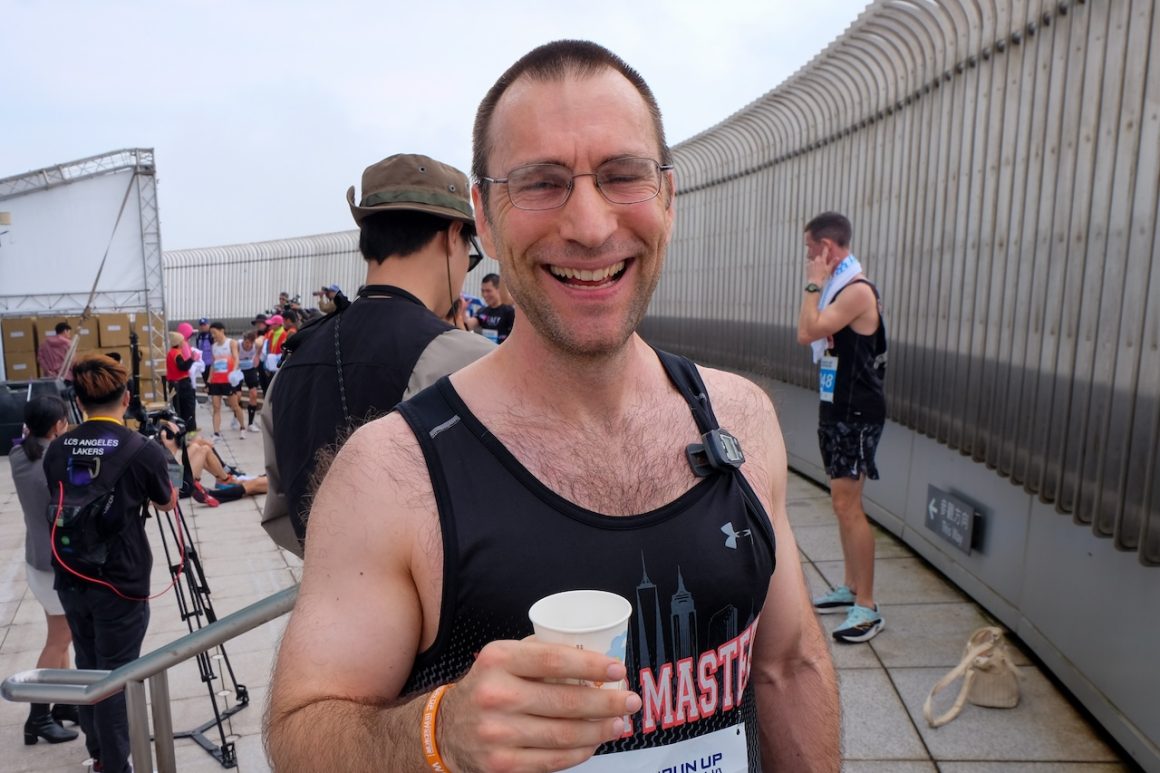

Alex Workman, an elite runner from the US who has visited Taiwan several times outside his running duties, looked over Taipei from the 91st floor. The clouds were finally dispersing, and he had a moment to relax before the second round.

It’s a pity that so few of his fellow elite runners will have time to enjoy the city, he said. Many of them were to fly out a day or two later, usually for a brief stopover at home before the next World Tour event in two weeks.